The AI & Robotics Technology Park, or ARTPARK, in Karnataka, India, is advancing data, technology, and AI across three primary workstreams: startups, platforms, and skilling.

In Startup@ARTPARK, the organization is providing incubation, acceleration, and mentorship for deep-tech startups at different stages of their growth journey. In Platforms@ARTPARK, foundational resources like data, open source models, data, and model pipelines are developed that enable research in Indian context and empower startups to create and scale their ventures through a multi-disciplinary approach. In Skilling@ARTPARK, the organization provides skills development programs that empower individuals and build capacity in the field.

It’s a tall order, providing that kind of full-service support, especially at a time of rapid development of new machine learning and artificial intelligence systems. However, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, it became clear to the ARTPARK team that this approach is more essential than ever. This commitment to skilling and capacity building carries the potential to not only grow new companies but to advance meaningful social change.

Areas with robust reporting systems skew the data driven decision making and those without it, tend to get left out. Leveraging computational and AI-based techniques combined with advances in environmental surveillance, satellite-based technologies, especially in domains of climate and health, there is a great potential for context-specific and evidence-based interventions.

Rohit Satish, Director of Data initiatives, ARTPARK

The Challenge

ARTPARK began during the early days of the pandemic within the Indian Institute of Science campus. Many of the organization’s current team of 16 were working in some capacity on COVID-related issues.

At the time, Dr. Bhaskar Rajakumar — now the ARTPARK Program Director of health initiatives — was working with the government of Karnataka, setting up the war room and data systems for the management of the disease for nearly two and a half years.

“Until COVID, my exposure to data science was limited,” he said. “The dependency on data-driven decisions in healthcare was minimal and, because of that, there was a bit of negligence in implementation of data systems.”

Like many in healthcare and government, Rajakumar got a crash course in data science, and he quickly saw an opportunity for better data collection, better data quality, better systems for processing and analysis, and ultimately better health solutions.

ARTPARK wanted to keep the momentum going.

“COVID gave all of us a lot of exposure to what is possible,” said Rohit Satish, the director of health data initiatives. “We asked, ‘How can we sustain the interest in leveraging data science in public health?’ How can we take this forward? There was interest at government levels and in research and academia”

ARTPARK works across several areas, including advanced manufacturing and autonomous vehicles, robotics, and large language models. However, as COVID began to recede, the team saw how their early work in tracking the disease and conducting predictive modeling for future outbreaks could be applied in new ways.

I’m glad that there has been more acceptance over time on the value of data-driven initiatives and, personally, I’m happy to see how data is helping solve big problems.

Dr. Bhaskar Rajakumar, Program Director of Health initiatives, ARTPARK

The Solution

Progress came in the form of an expanded emphasis on health data and exploring the critical intersection of climate and health crisis, prompting ARTPARK to join as a host organization within data.org’s India Climate and Health Data Capacity Accelerator.

“That is where dengue emerged as a priority disease,” said Rohit.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the incidence of dengue has grown dramatically around the world in recent decades, with reported cases increasing from 505,430 cases in 2000 to 5.2 million in 2019. A key driver of the increase in this mosquito-borne illness is climate change. Warmer global temperatures and increased precipitation have yielded ideal conditions for mosquitos. Globally, the economic burden of dengue is expected to be around $ 9 billion every year.

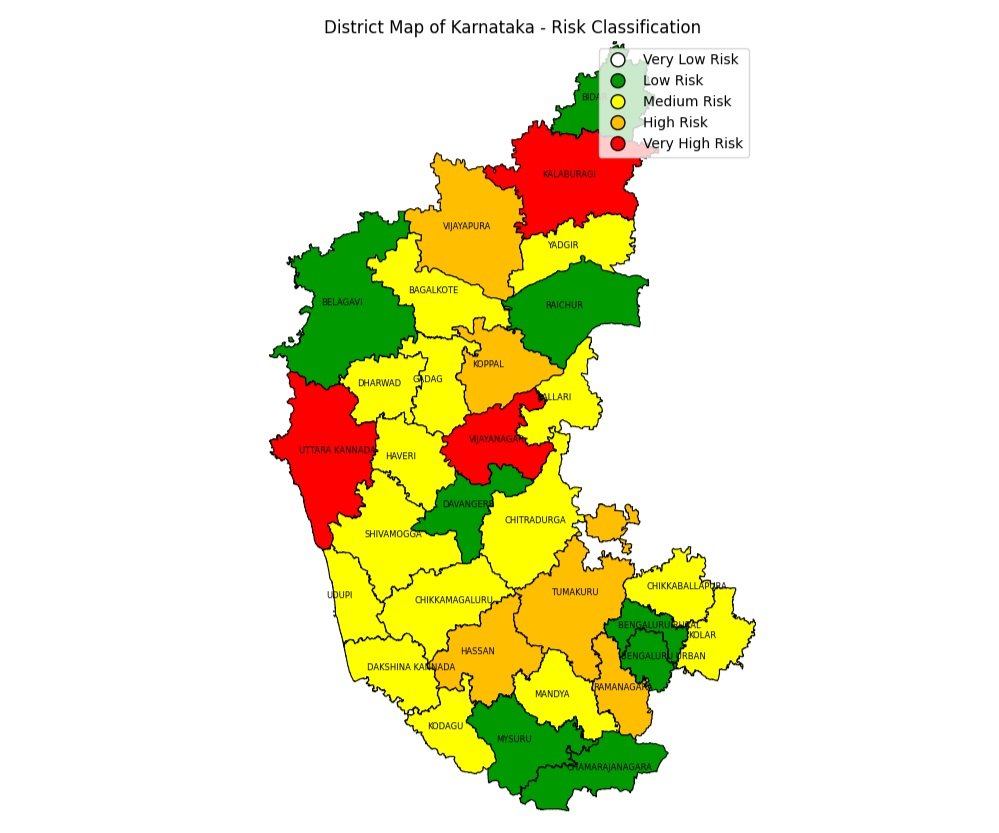

“This is an important problem and also a problem where proactive actions can control the outbreak,” Rohit explained. “There are some interventions that are possible with dengue, like source reduction activities, which are relatively low cost and can be informed by data science models.”

Building on the improved collection methods and data analytics and predictive modeling established during the pandemic, ARTPARK is applying those systems to dengue in close collaboration with leading experts from Indian Institute of Science, International Center for Theoretical Sciences (ICTS-TIFR), Bengaluru, and Northeastern University. Instead of relying on hard-copy paperwork, where frontline workers are identifying mosquito larvae breeding spots, they can now upload a photo that is tagged with geospatial data. Add in the public health data along with publicly-available topological and meteorological data, and the ability to identify risk for dengue–and subsequently deploy resources–is greatly enhanced.

Best of all, Rohit says, you can use that publicly available data to get a broad understanding of where outbreaks may occur, regardless of existing capacity. Areas with minimal reporting are often the communities with greatest risk.

“The model is as good as the data that it gets. If there are areas that do not traditionally have a robust data reporting structure, then the traditional models will miss that there may be outbreaks in those regions,” he said. “ Areas with robust reporting systems skew the data driven decision making and those without it, tend to get left out. Leveraging computational and AI-based techniques combined with advances in environmental surveillance, satellite-based technologies, especially in domains of climate and health, there is a great potential for context-specific and evidence-based interventions.”

With the experience of creating frameworks for improved monitoring and preparedness on dengue, ARTPARK is now looking at other issues at the intersection of climate and health, like tracking the incidence of additional vector-borne diseases like malaria, and exploring the correlation between heat waves and health conditions.

They also hope to expand into other geographies, helping to inform public health policy and empowering frontline workers and patients at the individual level.

“I come from an engineering background, building products and building solutions,” Rohit said. “What matters most to me is impact. How many people does it affect? When we are talking about data science and public health, the scale of impact is very high.”

The Takeaway

The scale of impact is high, yet the depth of expertise needed is broad. Both Rohit and Dr. Rajakumar underscored the interdisciplinary nature of their work. Workforce development is a key component of ARTPARK’s approach, and their focus on skilling extends beyond data scientists to students from public health and communications, among others.

Dr. Rajakumar said he’s a perfect example of why the field of data for social impact must broaden its network.

“I have been working as a healthcare professional for many years, and I always wondered why this knowledge was not part of my training,” he said. “This data helps me understand the disease better and it helps me understand the population better.”

Through its collaboration with JPAL curating and hosting one-year fellowship opportunities, as part of the the Capacity Accelerator Network, ARTPARK is committed to integrating data science into more educational and career pathways, including in medical training for healthcare professionals like Rajakumar.

“The next generation of leaders, the next generation of health practitioners who are coming into the field are interested in learning more about data-driven initiatives,” he said. “I’m happy that there has been more acceptance over time on the value of data-driven initiatives and, personally, I’m happy to see how data is helping solve big problems.”