Andrew, a graduate in Applied Statistics with Computing from Moi University, brings a unique mix of professional experience and self-driven data science projects.

Read moreNurturing Skills and Partnerships for Meaningful Impact: ICON Data and Learning Labs’ (IDL) Journey in Implementing and Scaling IMTA-Based Ecological Farming

Download the Case Study

Introduction

Andrew Karanja Njiyo, a Capacity Accelerator Network (CAN) Africa data fellow now with ICON Data and Learning Labs (IDL), begins his story with Atieno, a woman working on a rice field in Ahero, Kenya. Though she has no legal claim to the land, Atieno bears primary responsibility for tending the field and supporting her household. When floods strike, she loses not only her crop but also the income and food her family depends on. Reflecting on his work to promote ecological farming across Kenya, Andrew says Atieno’s story grounded his understanding of how climate impacts unfold and strengthened his resolve to help improve the lives of those most affected.

For Andrew, she embodies both vulnerability and resilience. Despite the lack of land ownership, erratic climatic conditions, and the gendered burdens she faces, caring for her family is a key priority. Atieno’s story mirrors the everyday realities of many women working in agriculture, playing a critical role in sustaining their communities and ecosystems, often without the meaningful support needed to do so.

Climate Vulnerability and Gendered Burdens in Kenya

In August 2024, 13.6 million people in Kenya grappled with inadequate access to food. With intensifying climate shocks—including erratic rainfall and rising temperatures—food insecurity is expected to worsen in Kenya, putting millions at risk.

Amid this escalating crisis, livelihoods are under threat, especially in agriculture, where women shoulder a disproportionate burden to cultivate and feed their families. As of 2019, women comprise 60% of Kenya’s agricultural workforce and contribute 70-80% of food production. Yet, they hold just 2% of land, according to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (2019). As climate patterns shift faster than ever, their work and daily lives grow more difficult, with their ability to provide for their families threatened.

Recognizing the intersection of gendered vulnerability and climate stress, the IDL team advances a data-driven, locally grounded approach to build resilience and secure livelihoods. With a focus on farm productivity, food security, and nutrition, which are directly linked to health, IDL uses data to understand ground realities, steer work with communities and government partners, and shape agricultural reforms. Therefore, data serves not only as a lens for understanding today’s challenges but also as a foundation to scale effective interventions with support from stakeholders.

Guided by this philosophy, the team turned to the principles of Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA) to promote cultivation combining rice, fish, and indigenous vegetables for more sustainable farming systems.

IMTA as a Pathway to Resilience

MTA is an approach that combines different species like pellet-fed fish, seaweeds, shellfish, and sea cucumbers within the same farming system. In this setup, the waste from one species becomes a resource for another, creating a balanced ecosystem where nutrients are recycled, and environmental impact is minimized. Based on IMTA principles, farmers practicing monocropping can shift to cultivating multiple species, including rice and fish in one setup. Through diversification, households can reduce waste and their vulnerability to the failure of a single crop or species. This in turn can maintain food security, stabilize incomes, and potentially enhance women’s access to resources and their participation in decision-making1. Recognizing its benefits, research and implementation of IMTA is being undertaken across countries, with systems ranging from experimental setups to commercial farms. As of today, China leads in large-scale IMTA implementation, with widespread rice-fish and rice-shrimp cultivation supported by government institutions2. While IMTA faces barriers to adoption including operational complexity, lack of technical expertise, difficulties in species selection, and scalability, it remains a promising approach to enhancing farm productivity and linked outcomes.

The Pathway to Scalable, Sustainable Farming

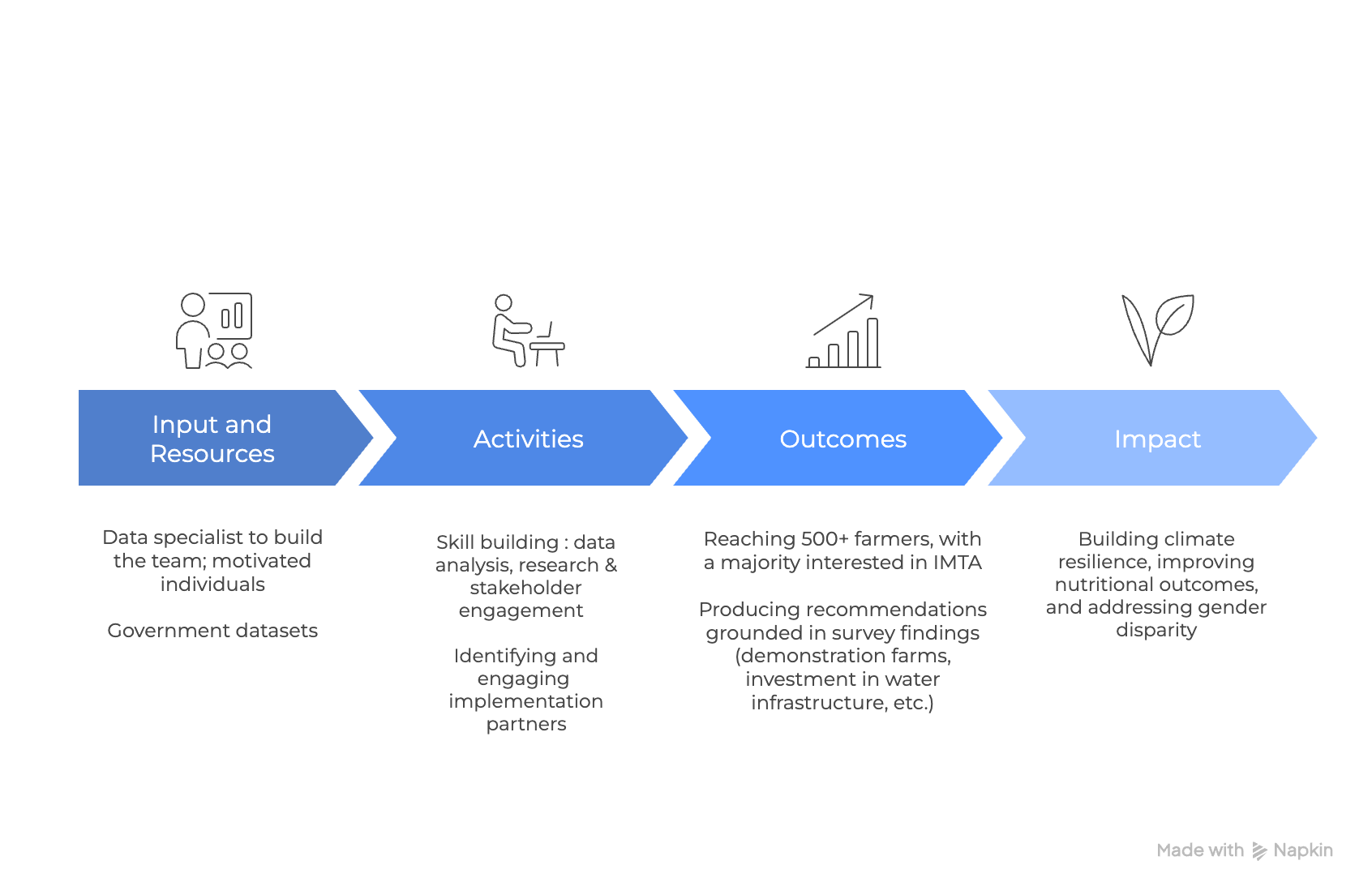

By combining context-specific knowledge with the right expertise, this ecological farming approach can be scaled to create sustainable and resilient food systems in diverse regions. To translate this vision into practice, Zeddy Misiga, a former CAN learner and founder of IDL, saw the need for technical expertise and realized the network could help bridge that gap. Through CAN, he met Andrew, who joined the team as a lead data specialist and took charge of building the data systems needed to inform and expand the work on the ground.

Along the way, Andrew’s role expanded beyond designing these data systems to nurturing talent and engaging relevant implementation partners. With evolving responsibilities and new challenges came valuable insights and lessons, pertinent for organizations tackling similarly complex challenges in the social sector. He quickly realized that technical skills alone weren’t enough. Success required a team capable not only of converting complex data into actionable insights, but also of engaging the right partners to translate those insights into effective action on the ground. “You can have a clear vision for your project, love your work and be good at it, but if you’re not able to communicate it effectively to external stakeholders so they see its value, it remains just a project for you,” Andrew reflected.

In light of this realization, Andrew carefully built a team combining technical expertise, research acumen, and communication skills under Zeddy’s guidance. By promoting skill development and ownership, they enabled the team to turn insights into strategies for sustainable farming, along with external partners. Government agencies contributed critical datasets, while civil society organizations, including farmers’ associations, helped promote holistic farming practices on the ground—forming a network where talent, trust, and evidence came together to promote ecological farming successfully. The network’s work goes beyond reforming cultivation, creating ripples of change that strengthen climate resilience, support women, and enhance nutrition in Kenyan communities.

The Implementation Puzzle: Navigating Complexities

Advancing the IMTA-based model demanded that Andrew and the whole team extend beyond their defined responsibilities and adapt to navigate evolving challenges. Andrew highlights several tasks the team undertook together, reflecting their dynamic approach:

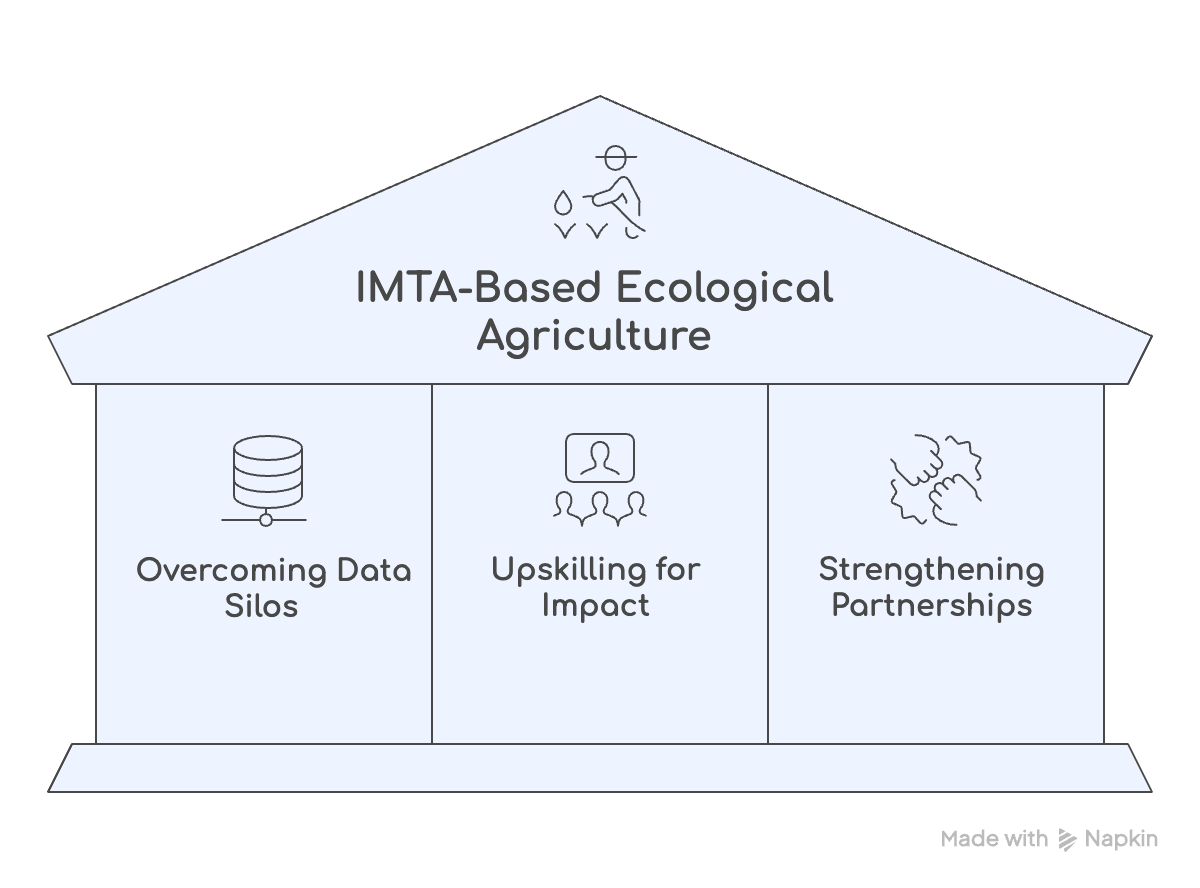

Overcoming data silos:

When Andrew was first onboarded as the only lead data specialist, his initial task was to understand what challenges farmers were facing. With data scattered across multiple sources, the IDL team needed to connect with the right partners, build trust, and encourage the exchange of relevant information. They reached out to the Kenya Agriculture and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO) and the irrigation department, for instance, regularly following up to draw relevant information. Emphasizing that data is most likely to be shared when its value is made crystal clear, Andrew said: “Part of [our work] was bringing them the evidence, showcasing its [their datasets’] value, what we could do with it, and the benefits they could gain from it.”

Going beyond data compilation, Andrew and his team worked with partners like the TINADA Youth Organization to conduct a baseline survey capturing the perspectives of 510 farmers. While government datasets shed light on aspects like land use and livelihoods, they offered little insight into farmers’ knowledge, their willingness, or capacity to adopt new cultivation practices— gaps the baseline survey was designed to fill. This survey revealed a clear disconnect: although 57% of respondents saw the value of integrated rice–fish farming, only 19% practiced it, indicating that the key barrier wasn’t resistance from farmers but a lack of knowledge and support. Beyond highlighting barriers to crop diversification, the survey exposed a stark outcome of current farming practices: 97% of households had poor dietary diversity, typically consuming fewer than three food groups.

After drawing essential data covering crop cultivation patterns, irrigation, and related factors, Andrew initiated the next phase: triangulating datasets, harnessing AI for deeper insights, and mapping patterns through geospatial analysis. Over time, he built a team of 4 data specialists to perform these functions and transform fragmented data into actionable, localized insights.

Upskilling for Impact:

As the team of data specialists began to see a fuller picture of what was happening on the ground, Andrew directed his focus toward building skills and awareness across the broader team. He organised various sessions with all 14 members of the team to introduce key data-science concepts and demonstrate their practical applications. The sessions, shaped by feedback from Andrew’s CAN peers, covered themes including data collection, quality and validity, data cleaning workflows, and predictive analytics.

While nurturing the core team of data specialists, he remained mindful that the broader team also needed to absorb these theories and develop these skills. After all, they would be responsible for absorbing and communicating the value of this innovative approach to people outside the team. Leah Gloria, Program Manager at IDL, expressed her appreciation for the upskilling efforts and intrinsic motivation, saying, “Because of the project, I’ve started learning data science on my own. I want to understand the nitty-gritties so I can help effectively, and so Andrew doesn’t have to spend a whole day explaining concepts. I’ve seen this growth in myself and across the team during meetings, training, and webinars”. Beyond training the IDL team, Andrew supported partners in improving their operations aimed at improving outcomes on the ground.

Strengthening valuable partnerships:

As noted earlier, cultivating strong, trust-based relationships with organizations like KALRO and other government agencies proved invaluable, providing access to critical information that guided the intervention. At the same time, partners such as the TINADA Youth Organization were instrumental in promoting changes in farming practices through community dialogues. IDL’s collaboration with these partners exemplified a symbiotic relationship: For instance, while Andrew and his team trained TINADA’s team of 39 data collectors, the latter offered essential qualitative insights and context drawn from their deep experience in Kisumu County.

Enabling Meaningful Change: Tangible Gains and Lived Experiences

Through this initiative, a young, diverse team was nurtured, blending technical expertise with a genuine belief in the intervention’s impact. The team was purposefully guided by leaders, enabling them to translate data into substantive change on farms, indicating the broader significance of talent development and data-driven approaches.

By integrating government datasets with farmers’ firsthand experiences, IDL and its partners conducted a detailed analysis of vulnerability and resilience, shaping a targeted intervention across 3 demonstration farms in Ahero. About 88 farmers, organized into six clusters, have begun adapting their cultivation practices to include indigenous crops like black nightshade, amaranth, and spider plant, alongside fish and rice. At this juncture, they continue to document tangible improvements on the ground, bringing them to life through storytelling, paving the way for broader adoption of the model.

Although the initiative currently operates on a limited scale, with only a few households practicing integrated farming, stakeholders are already seeing promising results. According to Douglas Otieno, Executive Director at the TINADA Youth Organization, farmers involved in the pilot have reported better yields, income, and nutrition. He notes, however, that broader implementation and stronger infrastructure support will be essential to realizing the full potential of this approach. With continued support, implementation, and systematic measurement, IDL and TINADA are confident that improvements in community health will become evident over the long term.

Beyond enabling better health outcomes, Douglas Otieno also highlights how scaling this project can bolster community-led governance: “If this project is upscaled to include many more households, we will see more community empowerment. What’s most important is putting a strong system in place, working closely with the relevant government ministries, the provincial administration, and community leaders. Localizing the agenda means the community must plan for itself. This creates an ecosystem of stakeholders who can work together as a team”.

A Note for Teams Making Change Happen

Investing in talent development empowers teams to take initiative, learn actively, and lead with purpose. Reflecting on how they built the team for this project, Zeddy Misiga, notes: “I’ve noticed that bringing in experts can solve immediate issues, but many are driven by monetary incentives and may move on when they receive better pay. Fresh graduates, by contrast, come in with passion and new perspectives. They may initially lack the technical know-how, but with training, they tend to take ownership of processes and buy into the organization’s vision. This approach is crucial—not just for managing wages in [a small social-sector] organization like ours, but for ensuring we have people who are motivated and aligned with our goals.”

IDL’s partnership with data.org’s CAN through the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data (GPSDD) reflects its focus on nurturing talent. Through the CAN training in Africa, Zeddy deepened his understanding of how data is key to generating insights and evidence for decision makers, especially in climate and health. After the training, he was encouraged to bring Andrew in as a CAN Fellow to help address a real-world challenge at the intersection of climate and health. Then, drawing on Andrew’s expertise as a purpose-driven CAN fellow, IDL built data systems to understand local needs and track farming outcomes, while also strengthening skills within and across the organization. Essentially, the benefits of partnering with initiatives like CAN extend beyond effective project implementation to empowering local actors, boosting efficiency, and reducing long-term reliance on a small group of experts. The hope is that, over time, farmers like Atieno will drive lasting community efforts to strengthen food systems through knowledge exchange to influence farmers’ decision-making behaviors and practices.

In complex, multi-stakeholder initiatives, cultivating skills and nurturing partnerships are key to leveraging data for lasting impact, an approach IDL not only believes in but actively practices.

This case study is brought to you by:

- Integrated farming can help women sustain and stabilize their livelihoods by diversifying income and reducing risk. But its potential to truly empower depends on whether women have access to assets and markets. Without these enabling factors, such systems may build resilience without changing who holds decision-making power. ↩︎

- China has emerged as a frontrunner in implementing IMTA, with strong government backing enabling rice–fish and rice–shrimp cultivation to flourish across both freshwater and marine environments. In contrast, IMTA in other countries remains mostly experimental or small-scale: Norway and Canada have tested salmon–seaweed–bivalve combinations, while Indonesia has piloted multi-species cage systems. Despite global research and interest, large-scale commercial adoption outside China is limited. ↩︎