Sitting in a classroom at Yale University in 2014, Ruchit Nagar listened to professors Joseph Zinter and Robert Hopkins lecture on the importance of human-centered design. You need to meet people where they are, they said, and deploy solutions that are technologically, economically, and regionally viable, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

The course, “Appropriate Technology for the Developing World” was structured around a challenge issued by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to develop novel approaches to address the world’s immunization gap.

More than a decade and over 45 million beneficiaries being tracked, it’s clear that, for Nagar, the challenge meant more than a grade on his transcript.

The Challenge

In 2023, over 14.5 million children under the age of one worldwide did not receive basic vaccines, according to the Centers for Disease Control. This alarming statistic, which places one in five children at heightened risk of death, disability, and illness from preventable diseases, reflects a significant increase compared to pre-pandemic levels. Since 2019, the global immunization gap has widened by nearly 2.7 million children.

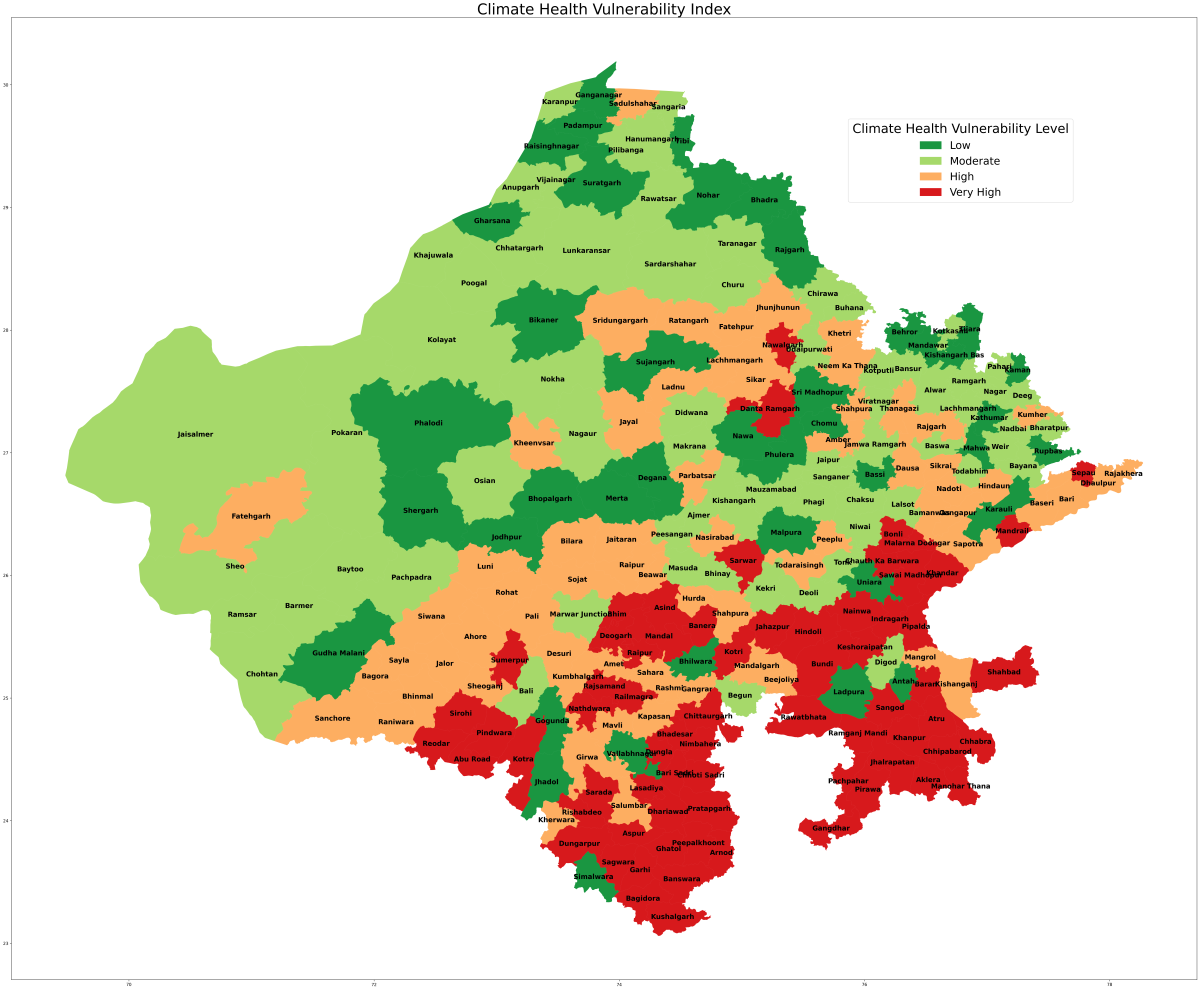

The majority of these children, often referred to as “zero-dose children,” reside in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), with over half concentrated in just 10 countries. India is among these nations, particularly in its remote communities, where challenges such as lack of data, accountability, and access to healthcare services exacerbate the immunization gap. Addressing these issues requires solutions that can function in offline settings to reach the last mile effectively. And with growing concerns around the intersection of health and climate, such as malnutrition from heat stress and increased vector-borne diseases, the stakes for timely interventions became even higher.

Recognizing these challenges, Khushi Baby identified a broader need for innovative platforms (Community Health Integrated Platform) that address both public health and climate-driven vulnerabilities.

The Solution

“It’s not the typical class project,” concedes Nagar, who went on to earn his master’s in public health at Yale and later his medical degree from Harvard Medical School. “On the digital health adoption front, we are one of the frontrunners in India.”

We do need to grow the field, and the best thing that we can do is generate awareness that data science skills can be applied to big public health datasets to solve problems that are in our own communities.

Ruchit Nagar, MD CEO and co-founder Khushi Baby

That may be an understatement. Khushi Baby has grown into a 95-person team that now serves as technical support partner to the Department of Health and Family Welfare in the Indian states of Rajasthan, Maharashtra, and Karnataka. But that reach didn’t happen overnight. Khushi Baby first applied its digital health services to maternal and child health, tracking ANC and immunization coverage.

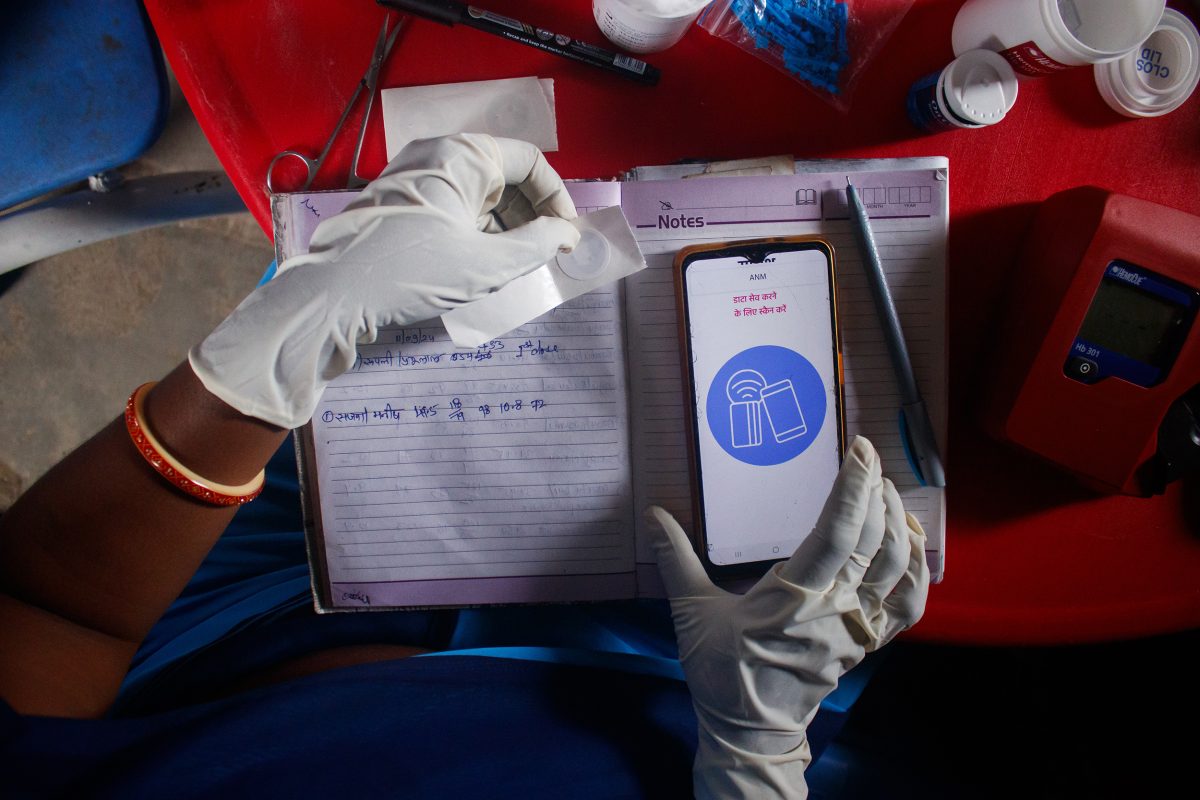

Then the organization worked with community health workers to design a Community Health Integrated Platform (CHIP), to be responsive to local needs and launched a user-friendly mobile application and dashboard that enables targeted public health interventions, including phone call reminders for parents to come into vaccine camps. Today, the platform’s user-friendly mobile application empowers CHWs on the ground with tools to track beneficiaries, collect data, and deliver timely health services. Simultaneously, health officials benefit from an AI-powered dashboard that provides real-time updates on program performance, helping them plan and implement interventions more effectively. CHIP integrates real-time data analytics, AI-driven insights, and geospatial tools to deliver targeted, impactful interventions.

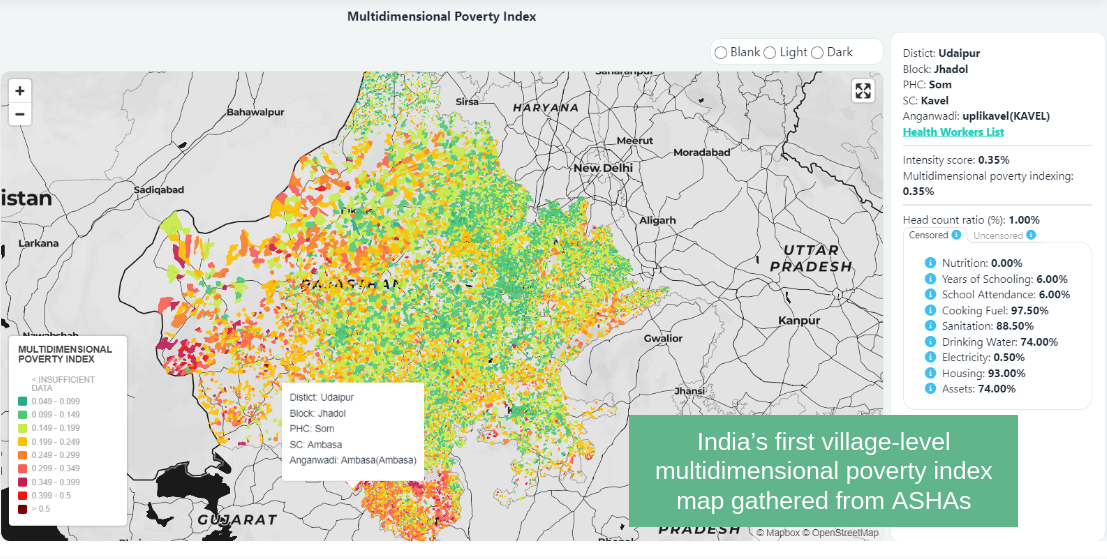

One of the unique benefits of CHIP is that it uses geospatial intelligence to map health inequities and allocate resources efficiently. By analyzing the first village-level multidimensional poverty indices, travel times to healthcare facilities, and disease hotspots, CHIP enables health officials to address systemic gaps. It has been instrumental in identifying high-risk areas for malnutrition, tuberculosis, and vector-borne diseases such as dengue and malaria. Furthermore, through its Climate Health Vulnerability Index (CHVI), CHIP integrates environmental, socioeconomic, and health datasets to anticipate climate-sensitive health risks, such as air pollution, heat stress, and vector-borne illnesses. These insights guide actionable interventions, down to the block level.

Khushi AI, an initiative of Khushi Baby, leverages machine learning models to predict critical health outcomes for beneficiaries and classify health workers based on data quality phenotypes, enabling enhanced training and support. In addition, a WhatsApp chatbot powered by a Large Language Model (LLM) is designed to improve the knowledge and information accessibility for community health workers (CHWs), ensuring they are better equipped to serve their communities.

So far, CHIP demonstrated its scalability by supporting over 70,000 CHWs and serving 46 million beneficiaries across Rajasthan, proving its resilience and adaptability in times of crisis.

By bridging gaps in public health service delivery, CHIP exemplifies how technology and data science can transform healthcare for underserved populations. It fosters government collaboration and trust through evidence-based policymaking and supports sustainable, data-driven solutions to public health challenges, including those posed by climate change. CHIP is not just a platform; it is a catalyst for equitable and timely healthcare.

One of the biggest challenges in public health is the disconnect between analytical expertise and deep public health understanding. Bridging this gap is essential to drive meaningful, data-informed decisions that address real-world health issues. By integrating analytics with public health systems, we can create sustainable solutions for the most pressing health challenges.

“It’s about creating a seamless chain, from health officials to community health workers, and from them to the vulnerable beneficiaries,” said Mohammad Sarfarazul “Sarfraz” Ambiya, Chief Data Scientist at Khushi Baby. “Reflecting on the scale we’ve achieved so far fills us with hope for driving large-scale, meaningful impact.”

“We are evolving into a data-driven organization, leveraging new public health datasets to empower public health officials with actionable insights to enhance their programs and target interventions more effectively,” said Ruchit Nagar, Founder of Khushi Baby.

He added, “We are at a critical juncture, similar to the challenges we faced during the pandemic. Our operations are now expanding beyond Rajasthan to Maharashtra and Karnataka, with the ambition of developing a scalable model capable of serving the entire country.”

As part of this expansion, Khushi Baby is integrating new health variables and outcomes while focusing on the intersection of climate and health. This includes studying the effects of air pollution on lung disease, the role of heat stress in exacerbating malnutrition, and the impact of rainfall and temperature fluctuations on infectious diseases—areas that Sarfraz described as “a pivotal focus for our future.”

The Takeaway

Sustaining meaningful growth requires recruiting, training, and supporting a workforce equipped with the right skills and a deep passion for public health. Sarfraz emphasized that this challenge is particularly critical in the field of public health.

“The key challenge is bridging the gap between strong public health expertise and advanced analytical skills. Building talent at this intersection is essential to drive impactful, data-informed solutions,” he explained.

Sarfraz is committed to enhancing data quality and expanding the evidence base while also focusing on nurturing the next generation of data practitioners for social impact. As a technical advisor for J-PAL South Asia in data.org’s India Capacity Accelerator Network, he actively mentors Khushi Baby’s growing team. Through the India Data Capacity Accelerator (IDCA) Fellowship facilitated by J-PAL, Khushi Baby welcomed a fellow in January 2024, with another slated to join in early 2025.

Though still early, the fellowship program has been successful at identifying candidates with the right policy and technical skills. Perhaps more importantly, it sources candidates with the right mindset in a landscape where social impact organizations can struggle to compete with private sector opportunities.

“Data science is an increasingly sought-after field, but the real challenge lies in fostering professionals who prioritize social good alongside their personal growth,” said Sarfraz. “We need individuals driven by a genuine commitment to creating positive change in society.”

But Khushi Baby is a testament to the opportunity and is working to illustrate that it doesn’t have to be one or the other – successful career or social good. What started as a university project has grown into a trusted resource for Indian communities, with a growing team that is applying data science skills to critical public health challenges. And those Yale professors that helped spark the idea now serve on the board of Khushi Baby, supporting Nagar’s work and continuing to inspire a new generation of purpose-driven data practitioners.

“We do need to grow the field,” Nagar says, “and the best thing that we can do is generate awareness that data science skills can be applied to big public health datasets to solve problems that are in our own communities.”