How fast is your internet? Is broadband available in your area?

These are the surface-level questions that have historically defined Internet access. But as the COVID-19 pandemic illustrated with stunning clarity, access and equity are not one and the same.

If access is about whether high-speed internet is even available where you live, equity is about whether people can afford to pay for internet, whether they know how to use it effectively, and how well the infrastructure they connect to actually performs. Internet equity thus is informed by many different factors at both the individual and community levels, from socioeconomic status and digital literacy to the built environment.

Understanding each of those factors and finding a systematic way to remove barriers to equity is at the center of the University of Chicago’s pursuit of mapping—and ultimately closing—the digital divide.

For decades, internet measurement researchers have focused on improving the performance of specific protocols and applications. It became pretty clear to me that the most pressing questions in networking were not purely technical but those that intersected with social and policy issues

Nick Feamster Director, Center for Data and Computing The University of Chicago

The Challenge

Nick Feamster is a Neubauer Professor in the Department of Computer Science at UChicago. He is also the director of the University’s Center for Data and Computing, and lab director at the school’s Network Operations and Internet Security Lab.

The team executing this work extends beyond Feamster’s colleagues in data science, however. It’s a cross-disciplinary group whose areas of expertise reflect the varied dimensions of the problem.

“For decades, internet measurement researchers have focused on improving the performance of specific protocols and applications. It became pretty clear to me that the most pressing questions in networking were not purely technical but those that intersected with social and policy issues,” Feamster said.

The root of the challenge is twofold. First, too few people in America have access to high-quality, reliable broadband internet. Second, we still don’t have an accurate understanding of just how widespread the problem has become.

Researchers and policymakers rely on readily available, but incomplete data that does not tell the full story. Broadband data from the FCC, for example, only reports access at the census block level. Current datasets also neglect to account for cost and focus on download speed as opposed to more relevant metrics like streaming performance.

Nicole Marwell is the co-principal investigator on the project. An associate professor at UChicago’s Crown Family School of Social Work, Policy, and Practice, and an urban sociologist, she underscores that it’s not just a question of the haves and have-nots when it comes to connectivity; the divide is visible between rural versus urban communities, rich versus poor neighborhoods, and every nuance in between.

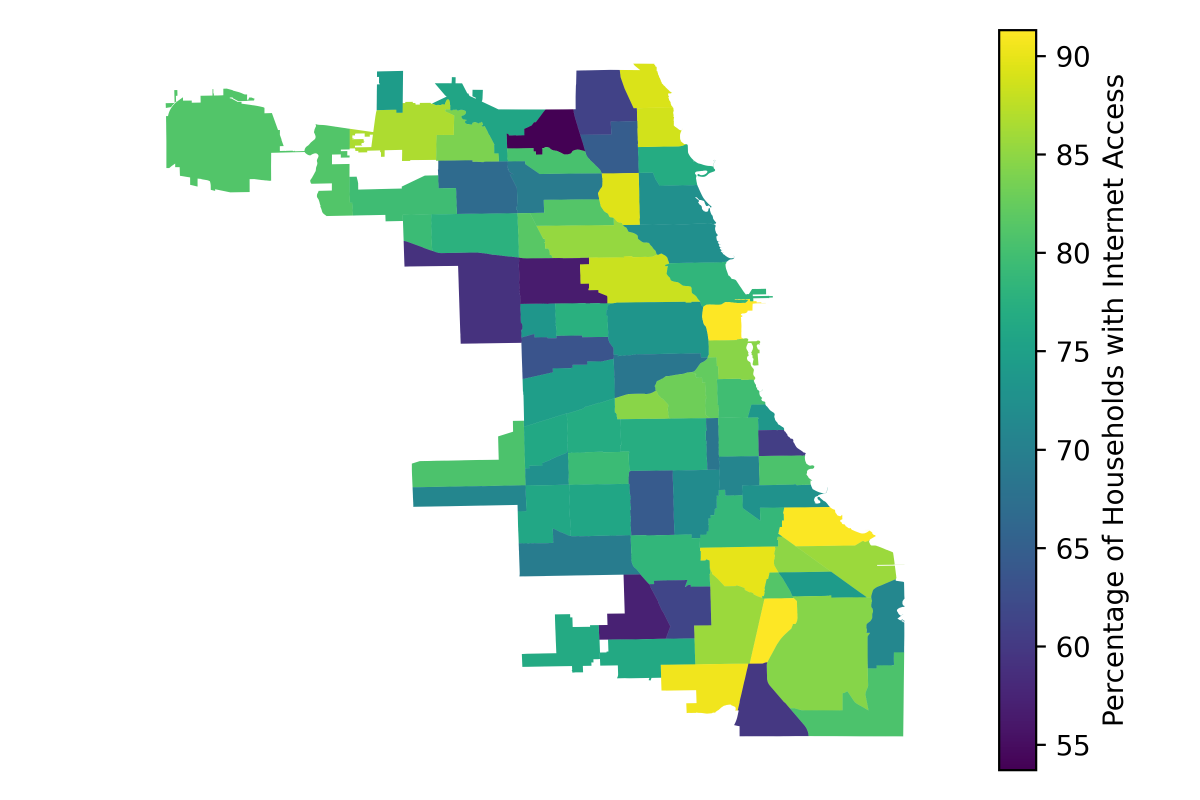

“A lot of the discussion is at the national scale, and the idea that we should have a benchmark that everybody, all across the nation, should be reaching. But as we are learning, the problem looks very different in different places,” she said. “You need a much more granular set of data to provide scaled-down, bespoke solutions.”

Grace Chu, the community project manager of UChicago’s Internet Equity Initiative, witnessed that need up close while working in local government in Cleveland, Ohio. She worked on an effort to expand access to broadband infrastructure and found a dearth of data to inform access strategies. Policymakers, she said, don’t know where to start.

Having the opportunity to address those gaps is what drew Chu to the project.

“We were trying to figure out how to spend government money on broadband infrastructure and for the most part didn’t have a lot of good data that we were working with. I thought this research project was really interesting because it helps address those gaps that a lot of policymakers are currently experiencing,” she said.

Then came the pandemic.

“Suddenly,” Feamster says, “everybody saw the problem.”

The Solution

While some sectors have been more aware than others of the digital divide, the pandemic put a spotlight on the inequities. Educators, for example, have long seen a “homework gap” with students in homes without internet access. When full communities were thrust into remote learning environments, the homework gap became a learning chasm.

Access to telehealth, professional environments, education—suddenly all aspects of our lives were dependent on connectivity.

Who gets to participate in society and who gets to take advantage of education and health care and other resources that are increasingly available online?” Marwell asks. “It is not just about internet access anymore, but internet equity. That has been a key lesson of the pandemic.”

That growing awareness and urgency have helped the team accelerate their work. In January 2021, data.org awarded $1.2 million as part of the Inclusive Growth and Recovery Challenge. This grant supports UChicago’s efforts to first focus on mapping the issue in their hometown, and then to translate those findings and learnings into a framework that can be shared and scaled.

Because what starts at the household level can be relevant on a global scale.

Architecture, building materials, topography, property management, and internet infrastructure—are some infrastructure considerations that go into the decision-making around the most effective way to connect. Is it an antenna on the roof or stringing fiber from the curb? Does the user subscribe individually or is it part of the rent?

The UChicago team is taking these hyper-local decisions and using them to inform what will become an open-source toolkit to inform cities and states nationwide. The project will also result in public maps and dashboards of the data they collect.

“That’s where we go from gathering data to building models, trying to move to a systematic understanding of how we help someone figure out how to go about doing this,” Feamster said.

The Takeaway

UChicago is poised to become a field leader in improving internet access. But they aren’t going at it alone. Among the lessons that they hope others in the data science and social impact spaces will learn from is that building robust, reliable new datasets takes collaboration and partnership.

And partnership starts with trust.

In Chicago, they are working with the City of Chicago Mayor’s Office, Chicago Area Broadband Initiative, South Shore Works, UChicago Consortium on School Research, and Chicago Public Schools.

“We are trying very intentionally to lift up the work that they’re doing, hear the things that matter to them, build our research response in a way that actually serves people as opposed to, ‘oh, this would be a great journal article’,” Marwell said. “You have to build relationships and trust. I feel like we’re starting to crest on that, but we’re 18 months in. If you’re going to do this kind of community, collaborative work, you need to be willing to commit that kind of time and persistence and resources.”

Collaboration with the community and within the cross-disciplinary team is key. Feamster hopes that this project can be a model not just for closing the digital divide, but also for broader applications of data science for social good.

“We will demonstrate that it is possible for computer scientists, for data scientists, to do work that has meaningful social impact and involves grappling with the fundamental challenges of those disciplines,” he said. “We’re starting with a hyper-local data point, but we are aiming to make the process—from sampling and collection to analysis and decision-making—scalable and replicable across other contexts and communities.”