In Lima, Peru, water is scarce, expensive, and inequitably distributed.

Lack of water access has reinforced deeply entrenched disparities in the city and further threatens the economic security and public health of families. Unsafe water is a leading risk factor for death, for example, and insufficient access affects everything from personal hygiene to proper nutrition to children’s health.

This reality is crystal clear to the people of Peru, yet evidence of its impact remains frequently undocumented. Just as water has been difficult to access, so too has data on its availability and expense, and this data desert makes it difficult to disrupt the status quo. With improved transparency, advocates in Lima believe that they can shift the public conversation from a known and reluctantly accepted fact to a call to action to increase equity and access.

The Challenge

“Lima is suffering,” says Dr. Liliana Miranda, executive director of Foro Ciudades Para La Vida, a national network set up as a non-profit civil association.

Miranda has been working on water access for more than two decades and sees how persistent and manifold the challenges have become. Quality of drinking water is one issue, but for even more Peruvians, access is limited altogether.

Out of the roughly 11 million people living in Lima, one million have no direct water connection in their residence. Another million have a water hook-up, but their water is rationed, sometimes as low as 30 liters per person—significantly lower than 80 liters recommended by the World Health Organization for adequate health and sanitation. Some households can access water only several times a week and often in a limited window. In some cases, that window could come in the early morning hours, like 3 to 5 a.m., further compounding the access challenge. Lastly, the cost is not equitable for all. If you do not have a direct connection, the expense to pay water tankers bringing water sources into the city is greater and less predictable.

This way of thinking is ruling our government and our companies in Peru. It’s racism, it’s discrimination, it’s classism and, of course, machismo. It’s something in the DNA of our institutional system, and it’s time we change that mindset.

Dr. Liliana Miranda Cities for Life Forum, Peru Observatorio Metropolitano del Agua para Lima-Callao

Not surprisingly, these issues are affecting primarily low-income households, and Miranda says very few residents feel they have the power to speak out and change the system.

“This information is all over the city; it’s well known by the authorities. People know the situation and they are, more and less, ‘that’s the way it is’,” she said.

Part of that lack of agency felt within the community is because the data quality is so poor. A sizable portion of the population is excluded from the existing government datasets, such as migrants and those who lack connection to administrative and political structures. Fenna Hoefsloot is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Twente in the Netherlands. Her research is focused on infrastructure for urban futures, and she sees this lack of transparency as a central element of improving the situation.

“If you don’t have an at-home connection and you don’t have a water meter at your home, then you’re not going to be represented in the data that the water company is going to be collecting,” she explains. “If there is a lack of transparency with regard to how many people are connected, it’s also difficult to hold the company accountable.”

Recognizing that gap, Hoefsloot began studying the use of digital technologies in water governance in Lima. That’s how she became connected to Miranda, as well as Dr. Andrea Jimenez, a lecturer in Information Management at the University of Sheffield who is originally from Peru and has likewise followed with great interest the growing urgency around water infrastructure in her native country.

Together, their team of university researchers and on-the-ground leaders set out to improve data quality and access in a way that could move the needle on meaningful change.

The Solution

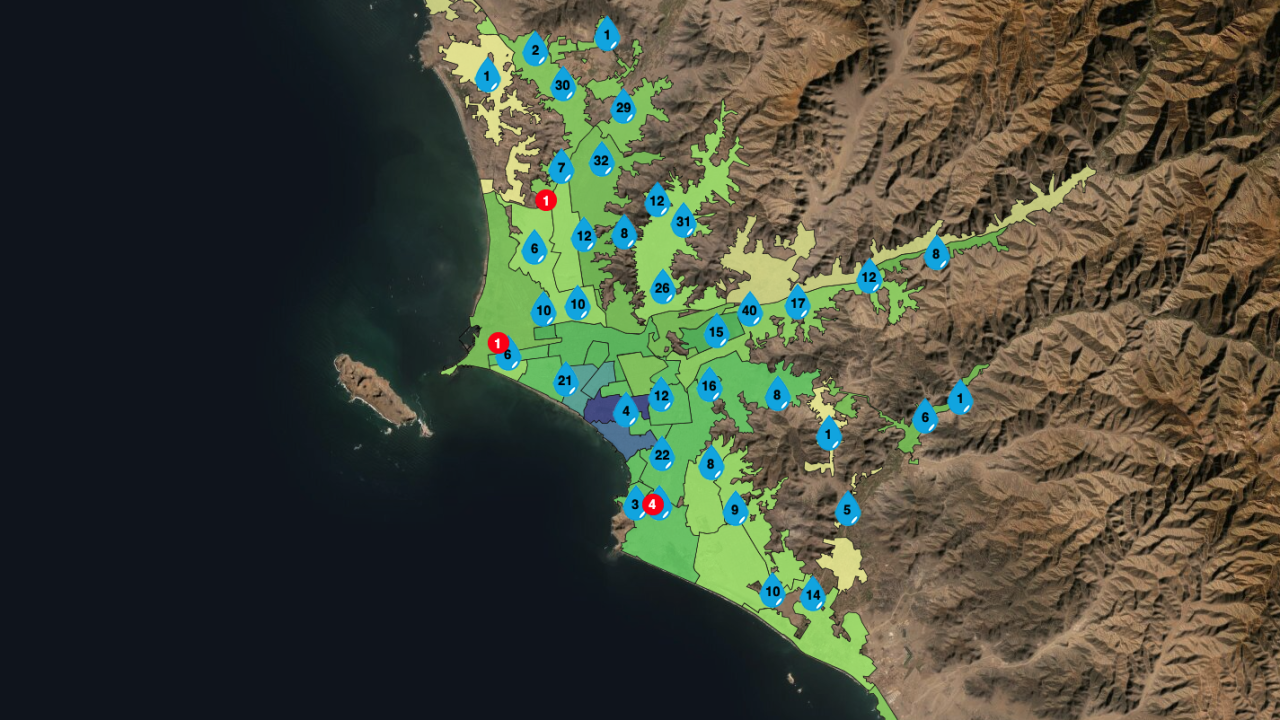

The Observatorio Metropolitano de Agua para Lima-Callao (The Observatorio) is the result of this collaboration. As a co-produced digital observatory for water and data justice, funded by the Knowledge in Action for Urban Equality program, the platform is nearing completion. The foundational datasets included are from existing data, which water companies and government partners have shared willingly.

“The Observatorio can be a bridge to help make some of their data more accessible,” Jimenez said.

More accessible, but not more complete. That’s why the team is already gearing up for an expansion of the platform that will accept user-generated data. But rather than making assumptions about the information that will be most useful to communities, the Observatorio team has been careful to create a community-designed product.

If you don’t have an at-home connection and you don’t have a water meter at your home, then you’re not going to be represented in the data that the water company is going to be collecting. If there is a lack of transparency with regard to how many people are connected, it’s also difficult to hold the company accountable.

Fenna Imara Hoefsloot Research Fellow (post-doc) University College London

“We convened focus groups to identify the problems. We asked them, ‘What would that platform look like? What indicators should we be collecting? What do you want us to do with the data?’” Jimenez said. “Everything has been designed with what they told us they wanted in mind.”

Households will be asked to complete a survey that assesses their water access and usage, either through direct user participation or through the support of civil service and community-based partners. By working with familiar organizations and letting them drive outreach, the team has prioritized trust-building in an authentic way. Already, volunteers in the effort are being assembled through university networks and Miranda’s extensive community connections.

“When people are involved in the making of something there is a sense of ownership and a sense of usefulness,” Jimenez added. “A lot of the projects you see can be very top-down and can feel extractive. Our whole purpose is that the Observatorio has the potential to influence future decision-making by making inequalities broadly visible.”

The Takeaway

The Observatorio has two target users. Water consumers in Lima can better organize and advocate with access to this information, and government and civil society organizations can better understand the scale of the problem and hopefully drive systems change

“There is power in having these numbers. All of a sudden, people can understand it in one glance—what the scale is—and they can use it to make decisions. It’s less easily brushed away,” Hoefsloot said. “If we manage to start this conversation based on the data that we generate, that could lead to some sort of transformation.”

Once completed, the community will also have full access to the data and have the ability to download the open-source code, opening up opportunities for other cities in Peru or beyond to adapt the platform for their own use.

A lot of the projects you see can be very top-down and can feel extractive. Our whole purpose is that the Observatorio has the potential to influence future decision-making by making inequalities broadly visible.

Andrea Jimenez Cisneros, Ph.D. Postdoctoral Researcher and Lecturer University of Sheffield

Without this kind of solution, Miranda knows firsthand that nothing will change. When she was starting her Ph.D. years ago, she went to the water company library to ask for the original master plan. The document, not digitized and full of dust at that point, had been completed in 1960. Written in black and white was the foundation for a system that has taken root today, in which water distribution is driven by the haves and the have-nots.

“This way of thinking is ruling our government and our companies in Peru. It’s racism, it’s discrimination, it’s classism and, of course, machismo,” she said. “It’s something in the DNA of our institutional system, and it’s time we change that mindset.”