St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Harris County, Texas, was the first medical center in the region to serve the African American community during segregation. It went through different iterations over the years—hospital, drug rehabilitation, outpatient treatment center—but it maintained its status as an icon of the community, a symbol of inclusivity at a time of division.

So, even after the hospital closed in 2014, and later sustained major damage from Hurricane Harvey, the community didn’t want to let it go. With the support of the neighborhood, a nonprofit developer came forward with a plan to preserve the property.

There was just one problem. Competing commercial interests were circling the increasingly sought-after area, and the community needed help to understand if the project was viable from an environmental perspective.

“Green light means go, red light means stop. The community really needed that kind of a quick tool.”

That’s the conversation that Danielle Getsinger recalls having with the developer, and it sparked a new idea for her small but mighty two-person team at Community Lattice.

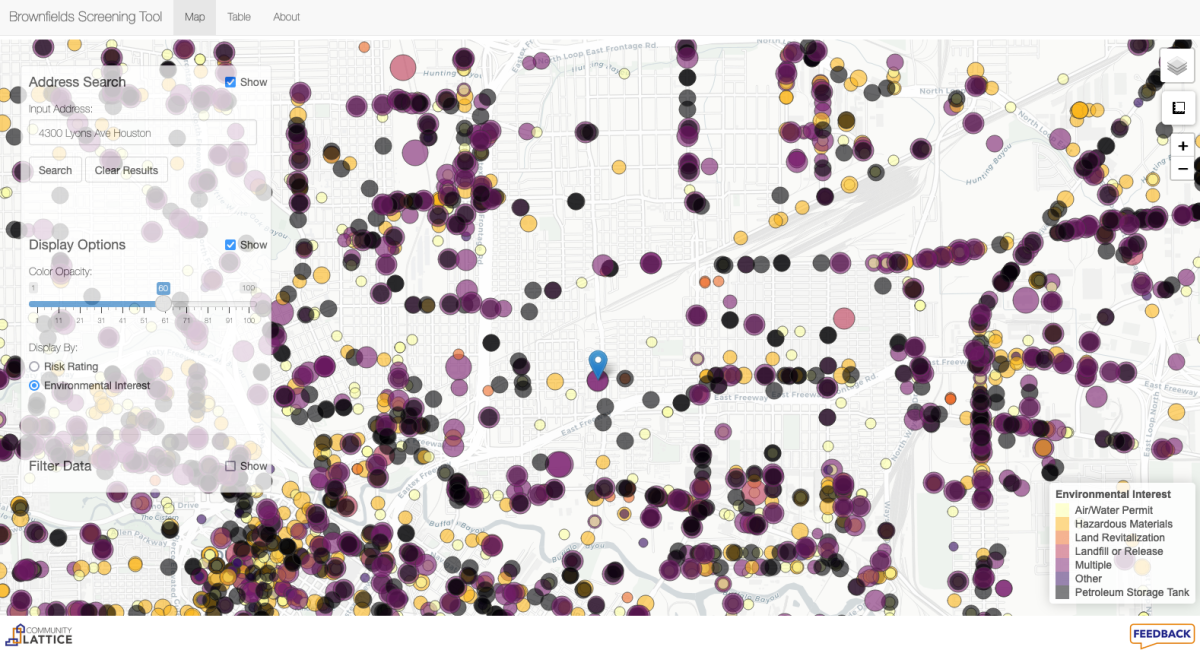

They began to develop an environmental records screening tool to make it easier for communities to identify environmental risk early in the redevelopment process in order to reduce the likelihood of encountering unexpected challenges on projects like St. Elizabeth’s. This would in turn enable community developers to identify brownfields redevelopment opportunities and secure necessary resources to clean up contamination.

You don’t understand things that you can’t see, that you can’t visualize. This tool helps the community visualize documented or potential pollution in their neighborhoods.

Danielle Getsinger Chief Executive Officer Community Lattice

The Challenge

Community Lattice uses data science to identify and mitigate environmental risk. The tools they develop in turn advance community development to foster more economically sustainable, socially equitable, and climate-resilient places.

In the case of the environmental records screening tool, the work begins in the organization’s backyard in Texas.

Austin, for example, is considered one of the top places to live in the United States. It’s a pride point that comes with strings attached, including continuous challenges around housing shortages and gentrification. With the real estate market at a fever pitch, developers and communities are often at odds with one another. Private investors are buying up desirable properties and creating uses that don’t necessarily serve the needs of the local community. Moreover, these private investors and developers have a leg up on community partners that want to preserve and restore properties in their area. Community organizers often lack the same capacity for researching, understanding, and mitigating environmental contamination. Historically, this hasn’t been an area of emphasis in development.

“If you can understand the reuse potential, the economic drivers, and the community drivers, why aren’t we assessing environmental risk at the same time?” asks Getsinger, the CEO of Community Lattice.

That is often easier said than done, however. Many communities, especially those in economically depressed and historically underserved urban areas, lack access to the data, tools, funding, or strategies they need to get projects off the ground. When community developers go after limited funding—like brownfields grants through the Environmental Protection Agency—too much time and money for the project is eaten up by paying for assessments and fact-finding.

Getsinger and her CTO partner Shannon Loomis want to level the playing field.

“Community developers are competing with gentrifying forces. They’re competing with the rapidly competitive market. They’re buying properties with cash in whatever condition they are to basically claim their territory that can be redeveloped for the neighborhood,” Getsinger said. “I fell in love with the solution of cleaning up environmental contamination through the process of repurposing properties to create community assets.”

The Solution

Community Lattice takes a data-driven and multidisciplinary approach to find and foster those hidden gems that build community pride. Working closely with government and community partners, they access publicly available environmental records through the Facilities Registry Service (FRS) to better understand environmental risk and qualify properties for EPA brownfields funding. The FRS is an open-source environmental records database used by many federal data visualization and analytical platforms like EPA’s EJSCREEN, the Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool.

Green light means go, red light means stop. The community really needed that kind of a quick tool.

Community Developer

However, these national tools only display select EPA records and exclude state records, which are critical for understanding environmental risk.

Community Lattice is not only including state records in their environmental records screening tool, but also working with EPA partners to better understand discrepancies in state reporting and advocate for inclusion of all data in the FRS. This data feeds into Community Lattice’s environmental records screening tool and reinforces a compelling—albeit not surprising—story. The areas most exposed to environmental risk are home to the most vulnerable and marginalized communities.

But by combining that information with parcel data at a community level, Community Lattice identifies potentially contaminated and underutilized sites. With this information, community-based organizations can pursue sustainable and inclusive redevelopment opportunities.

“You don’t understand things that you can’t see, that you can’t visualize. This tool helps the community visualize documented or potential pollution in their neighborhoods,” Getsinger said. “It’s going to advance transparency, and what I’m really hoping for is that it’s going to enhance the ability for communities to participate in Brownfields development projects and community planning.”

The Takeaway

The environmental records screening tool is still new, having just been piloted in October 2021, but early reactions have been positive from municipal partners who have seen the visualizations. The focus for the next year will be sharing the tool more widely, encouraging communities to use it, and making adjustments and enhancements based on their feedback.

From there, Community Lattice hopes to expand in two ways—what data is included, and how the data is being used.

The quality of the EPA data and sophisticated infrastructure of the FRS database has made development of the screening tool possible. To ensure environmental records are made available to communities, researchers, policymakers, and various stakeholders, Community Lattice will be advocating that EPA enhance their FRS with consistent state reporting nation-wide.

This will be a major focus moving forward, bolstered by the recent bipartisan Congressional action that has delivered the single-largest investment in U.S. brownfields infrastructure ever. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law invests more than $1.5 billion through EPA’s highly successful Brownfields Program.

“The quality and quantity of states reporting environmental records to the FRS is currently inconsistent. Ideally, we would like a new federal rule that would mandate states to share their records with the FRS to consolidate all data in one location,” Getsinger said.

Community Lattice is also excited to expand their partnership ecosystem and explore new opportunities for integrating the tool into resiliency planning at a time when environmental justice and climate action have never been more important.

“There’s so much work that needs to be done here,” Getsinger added. “A lot of our next year is going to be seeing how this can be used for vulnerability analysis, for climate action, and climate adaptation. We’re excited to kick off 2022 by integrating our data into Houston’s Resiliency Planning, national brownfields planning, and by helping community partners in Houston with building resilient urban agriculture thanks to a $200,000 EPA Environmental Justice grant.”

And, if things go according to plan and the tool is used like it was for St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, there will be more community groundbreakings in the future.